The Forgotten War Against Mick Skrijel by the Evil Corrupt SAPOL, VicPOL and NCA

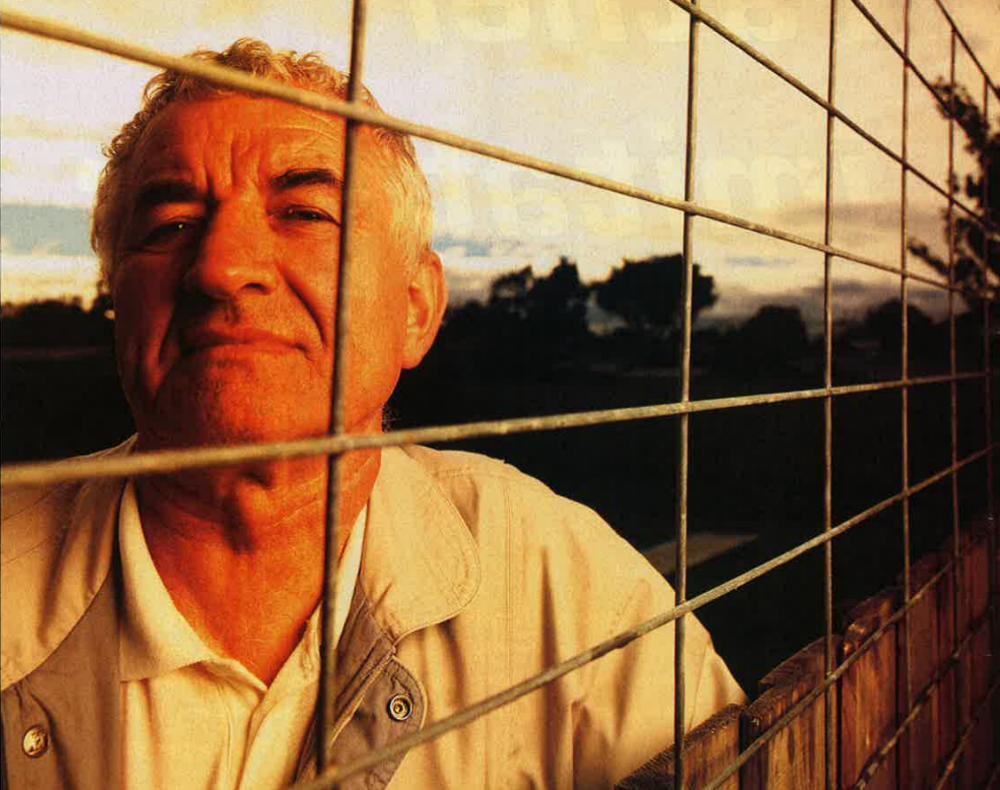

Honest fisherman Mick Skrijel, who was violently stalked, assaulted and falsely arrested after reporting a SAPOL-protected drug trafficking ring in South Australia's South-East.

Mick Skrijel Fights For Justice

by Hall Greenland

City Hub — 29 February 1996

This is the epic tale of a fisherman who did his duty as he saw it and got more that he bargained for: arson attacks (on his boat, his house, his wife’s car), a daughter menaced during a raid on his home, a drug bust and a police frame-up, jail, a successful appeal, a ransacked house, an intruder whose calling card was a shining bullet, unexplained firearms which appear and re-appear, an independent inquiry which recommended a Royal Commission, and a Federal Minister for Justice who can run but cannot hide.

Mellie ‘Mick’ Skrijel (pronounced Skreel) is a tough, cheerful 54-year-old who now lives in Sunshine, an outer suburb of Melbourne. When his odyssey began he was a fisherman in South Australia.

In March, 1978, while at sea off the South Australian coast he saw what he thought were fishing boats picking up heroin drops and subsequently reported it to the police at Millicent in South Australia. No busts and no arrests followed his tip-off.

Instead Skrijel got “unlucky”. His boat was burned to the waterline, his crayfish business was shunned, his home was invaded by masked men (his 12-year-old daughter, the only one at home, was terrorised), and finally his house was damaged by fire.

In 1984 he took the matter to the newly established National Crime Authority and the NCA began investigating his complaints, Skrijel was not satisfied with progress, grew suspicious, and by August-September 1985 was alleging that some NCA police (who he named) were involved in a cover-up.

Now a clear pattern of ‘coincidence’ began to emerge between his criticisms of police and his “bad luck”.

In October, Skrijel, who had a hobby farm near Digby, a small country town in Victoria, was himself busted for growing marijuana in a nearby State Forest.

The police who did the bust were the same NCA police Skrijel was publicly criticising. They charged Skrijel with cultivating and possessing marijuana, and possessing explosives and a sawn-off .22.

The case against him certainly looked like a set-up. Consider the sequence of events: On October 8 the police got their search warrants and began their round-the-clock surveillance of Skrijel at his Melbourne home and the marijuana plantation. Skrijel was in Melbourne until October 14 (which meant that the NCA police had unimpeded access to the Skrijel farm for a week). He travelled to his farm on October 15 and rather than maintain the surveillance on the plantation and Skrijel to see whether they could cateh him visiting the plantation, the NCA agents immediately swooped and arrested him.

And lo and behold, all the incriminating evidence needed to load him up was sitting smack in the middle of his farm shed waiting to be filmed by the NCA video operator. There was a cardboard box of marijuana, and alongside it sitting on the step of a ladder was a set of kitchen scales (without any finger prints, however). Close by was a piece of wood which forensic would later identify as being from the same length from which a seedbox found on the plantation was made. (The suspicious elements here were: the seed box was roughly made whereas Skrijel, a shipwright by trade, is a skilled woodworker, and the timber on the seedbox, found out in the open, was relatively unweathered.)

Despite all the apparent weaknesses, Skrijel was convicted by a judge and jury in April 1987. In this remarkable case the prosecution’s final address took 40 minutes and the hostile judge (the Court of Appeal later found he’d misdirected the jury) took more than a day. Among other things, the judge argued that Skrijel was mentally ill. Skrijel was sentenced to two years imprisonment and $200 for possession of the unlicensed .22 Cooey automatic pistol.

After he’d been in prison for six months, the Supreme Court upheld his appeal and ordered a new trial. He never got it, In June 1989 the Victorian Director of Police prosecutions appeared in court to say that they would not be pursuing the case, thereby aborting the Supreme Court ruling.

Skrijel has continued suffering from “bad luck” as Richard Ackland put it in the Financial Review last November:

“Mrs Skrijel’s car was destroyed by fire and the forfeited and unlicensed Coney pistol was ‘found’ back on his property in 1992. Earlier this month, his home in Melbourne was ransacked, a single shiny bullet was left next to his fax machine.”

The strange planting of the Cooey pistol—it turned up in Skrijel’s farm kitchen seven years after the police confiscated it and five years after the court ordered its destruction—was not the only firearm mystery in this affair. Two weeks after Skrijel’s 1985 arrest, the NCA took possession of a shotgun from an engineering factory where it had been left for modification in the name of Skrijel. No mention of it was made in the 1997 trial, yet when Skrijel took possession of his personal effects from the police after his appeal was upheld, the shotgun was amongst his property. He refused to accept it as his, and it has since disappeared without trace. Was the shotgun part of the 1985 frame-up which was later found to be superfluous, but not efficiently disposed of?

Skrijel was by this time convinced there was something very rotten in the NCA and appeared before the Joint Parliamentary Committee inquiry into the NCA in 1991.

The Committee recommended an official inquiry into the Skrijel affair but the Federal Attorney General’s department advised against such an inquiry.

In 1993, believing he had reached an official deadend, Skrijel initiated his own Civil action in the Victorian Supreme Court action for damages against the NCA.

Then, and only then, did the Federal Minister for Justice, Duncan Kerr, commission Adelaide barrister David Quick QC to investigate the Skrijel affair.

Quick’s final report was delivered to the minister last April. Although his report was heavily qualified, and handicapped by a suspicious Skrijel’s refusal to fully cooperate, Quick essentially found for Skrijel.

Quick considered that there was “good reason to suspect” that Skrijel had been framed in 1985. In lawyer’s language, he “strongly suspected that some person in authority had carried out acts with a view to incriminating or otherwise causing harm to Mr Skrijel”. He Was left “with a firm suspicion that fabricated evidence may have been presented in connection with the drugs and explosives charges.”

While he’d spent most of his time reviewing the post-1985 events, Quick did note that one of the S.A. police Skrijel had earlier alleged involved in the drug trade had since been convicted and imprisoned on drug charges (our note: the convicted cop in question was the late Barry Moyse, who ran a lucrative drug trafficking operation within SAPOL for years. Among Moyse’s numerous drug exploits was the use of his “Operation Noah” dob-in-a-drug dealer campaign to confiscate and resell drugs. SAPOL were extremely angry when golden boy earner Moyse was busted by the NCA. More recently, Moyse’s lawyer daughter Catherine was charged along with rotten magistrate Robert “Dodgey Bob” Harrop and corrupt SAPOL prosecutor Abigail “Abby” Foulkes for corruption offences).

He called for the Federal Government to set up a Royal Commission to investigate the NCA’s handling of the Skrijel affair-particularly the NCA’s bust of 1985.

Duncan Kerr dismissed the call on the grounds that “a Royal Commission is an extraordinarily expensive and time consuming process.”

Instead, Kerr tossed the case to the Victorian Ombudsman, who may or may not be able to discover something about the NCA’s Victorian Police “helpers”, but is in no position to investigate the Federal NCA.

What any inquiry would have to determine is whether the NCA police persecuted Skrijel solely because he’s a “troublemaker” or because some of them were involved in the drug trade. After the revelations of the NSW Police Royal Commission, which have implicated some Federal police in drug crimes, a full investigation seems justified.

Note: City Hub’s request for an interview with Justice Minister Duncan Kerr was refused.

Mick Visits the Minister

Mick Skrijel has joined in the Federal election campaign. He is back in Hobart this week in his quest for a Royal Commission into his longstanding tangle with the National Crime Authority.

He’s putting leaflets in letter boxes, telling his story on street corners, and is holding a public meeting.

He wants the voters of Hobart to dump local MP Dunean Kerr, the Minister for Justice, whose electorate is based on Hobart and who has refused him a Royal Commission. Kerr is worried enough to have had his own leaflet delivered to every Hobart letterbox. Under the headline “Smear Campaign”, Kerr wrote “Mr Skrijel appears to believe that as Minister for Justice I am part of a conspiracy to ‘protect criminals’. 1 preferred not to have to respond to these wild allegations, but I decided to write to assure you there is no truth whatever in the ridiculous claims being made against me and the staff of the Attorney-General’s Department.”

When Skrijel was in Hobart two weeks ago, Kerr threatened the local media with defamation writs if they allowed Skrijel to sound off with his “wild” charges. ABC Radio’s Annie Warburton consequently cancelled an invitation to Skrijel. A fearful Kerr also asked the Federal police to do an “assessment” on Skrijel.

On February 6 Annie Warburton got a visit from the Feds who among other things wanted to know Skrijel’s whereabouts. Richard Ackland in the Financial Review takes up the story: “She was asked by the AFP officer to get in touch with the whistleblowers’ organisation, ask them to contact Skrijel and invite him back to the studio on the pretence that another interview would be scheduled.”

“It was suggested that she string Sktijel along and find out his address in Hobart, so that the copper could go and interview him.” To her credit, Warburton refused and spilled the story to the media.

The Feds did catch up with Skrijel in both Hobart and in Melb6timne, asking him to keep his distance from Kerr.

Undeterred, Mick Skrijel is back in Hobart and talking to the voters.

The City Hub story barely scratches the story of the Mick Skrijel saga, in which he and his family had to flee South Australia due to the corrupt SAPOL and NCA, only for the harassment to continue in Victoria. Here are some more articles:

Mehmed Skrijel and David Berthelsen, Submission to the Joint Committee on the National Crime Authority, 1990

Hall Greenland, “Mick Skrijel fights for justice“, City Hub, 1996

Mick Skrijel, “Crime justice and Mr Kerr“, leaflet, 1996

Richard Ackland, “Policing a citizen’s right to expression“, Australian Financial Review, 1996

Richard Ackland, “Fishing tale with a sad catch“, Sydney Morning Herald, 1997

Max Wallace, “Fishing for the truth“, Alternative Law Journal, 1997

Mr Skrijel, appearance before the Joint Committee on the National Crime Authority, Parliament of Australia, 11 June 1997

Richard Guilliatt, “The man who won’t give up“, Sydney Morning Herald, Good Weekend, 1999

Mick Skrijel, letter to the Prime Minister, 2001

Hall Greenland, “Mick’s war“, The Bulletin, 2003

“Hell in Australia, the Mick Skrijel story“: Mick’s personal story (very long)